Of all the decisions that game developers and publishers make, none baffles me more than changing names for change’s own sake during localization. Altering a creator’s work requires justification: the name “Tina” in Final Fantasy VI was intended to sound foreign and mysterious to Japanese audiences but wouldn’t have that effect in North America, so it was changed to “Terra.” People can debate the legitimacy of the reasoning behind that change and explain why they don’t believe it was necessary, especially with the benefit of hindsight; they might say that names like Mario, Luigi, Link, and Cloud are universal, that the name “Cid” is a constant in the Final Fantasy series, or that Tales games regularly use names like Natalia, Chester, Lloyd, and Rita for both English and Japanese with few fan complaints. What no one can argue is the fact that reasoning for the name Terra existed. Thought went into it and so I don’t dispute her name change.

On the far opposite end is the inconsistency of Pokémon naming. For the most part, the series localizes names so that whether English-speaking players are six or sixty, they know that a Bulbasaur is a dinosaur with a bulb. However, the name Pikachu carried over along with other names and portmanteaus like Jirachi, Rayquaza, Lucario, and Pachirisu. The question is why they didn’t change and the answer is—a mystery.

Just as much of a mystery is why Japanese names that would already make sense to English speakers sometimes get changed. Above are a chinchilla Pokémon and its evolution, known as Chillarmy and Chillaccino in the Japanese games, but as Minccino and Cinccino in the English games. The question isn’t whether the changed names are good or bad, but why the changed names are. If anything, “Chillarmy” is likely more easy to pronounce for nine-year-old native English speakers than “Minccino”.

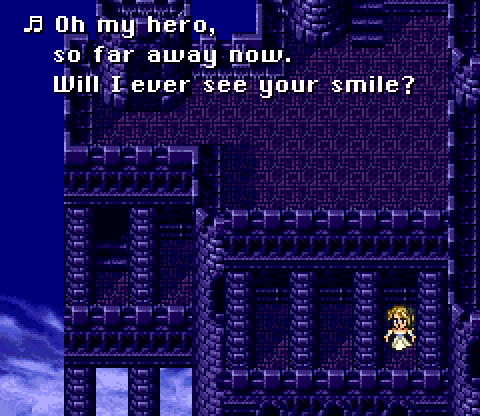

The Final Fantasy VI opera scene: my proof positive that nostalgia has little hold over me. I only needed one look at the GBA version to throw the above lyrics out of my heart.

“Because we can” is a poor argument to change lines—after all, you “can” also not change them—but I’m not a purist. I have my preferences only independently of faithfulness to the original. I don’t know or care which version of Dragon Quest IV is closer to the original, but I do know that I prefer the NES localization over the DS re-localization. I also know that, with only a couple of exceptions, I prefer the SNES localization of Final Fantasy VI over the GBA re-localization that Square-Enix certainly stated was more faithful.

Above all, I believe one thing about localizations: that they should see their ideas through. I may not like the all-over-the-map accents of Dragon Quest IV, but I admire that the team had a vision and ran with it to the greatest extent. Even though I didn’t like it once, that same willingness to change things worked wonders for me with Dragon Quest IX‘s alliteration-rich translation. If Cherry Tree High Comedy Club went all the way to whitewash every Japan-related reference out of the dialogue, I wouldn’t have liked that decision but I could at least say that it wasn’t a house divided. If only legendary Pokémon kept Japanese names and the names of ordinary Pokémon always changed, there would be a certain clarity to the series’ naming conventions.

Just as every spell or special move should be created with a purpose, every word in a game script should be put in with a purpose—and that holds true whether the word is being written on a blank sheet or translated from another language.

.png)