Ever since OUYA I’ve become something of a Kickstarter addict, backing 21 other projects. I believe that, no matter how much I give to others, it will all ultimately come back to benefit me too. Call it karma or call it reaping what you sow, but I’m interested in building a world where dreams come true. Who wouldn’t want to live in such a world?

This question is why I’m interested in Kickstarter-critical articles. Usually negative articles are written by people who think that Kickstarter is meant for investors or customers rather than people who support an idea, but a recent Rock Paper Shotgun post comments on the “peril” of Kickstarter nostalgia, saying that many Kickstarter mega-projects like Double Fine Adventure, Project Eternity, and especially Old-School Role-Playing Game are making crowdfunded fortunes with sales pitches about not innovating. I can think of several responses, but I’ll pick three.

1: Originality is understood by playing, seeing, or knowing about the game, not by explanations in the written or spoken word.

I’ve been taking notes of game sales pitches on sites like Kickstarter and Steam Greenlight. Below are just a few cases of game creators’ first one or two sentences of description; I could easily post twice as many.

I like all three of these games, but not because of their promotional writeups.

- 8-Bit Night, a retro platform game with a unique twist.

- Abandon Quest is an unconventional open world tactical role-playing game set in the magical pop-up book of Corderia.

- Akaneiro: Demon Hunters is a unique free to play Action-RPG adventure presented within a vivid and expressive hand-painted world.

- Aril is a unique action packed multiplayer strategy game for pc & mac.

- Bean’s Quest is a gorgeous 2D platformer with a twist!

- GravBlocks is a “twist” on a classic puzzle game formula.

- A fast paced 2D sidescrolling runner with a unique hat based health system, [H]atland [A]dventures delivers a unique, fast and beautiful glance into the world of the truly extreme hat collector.

- Perplex Beats is a rhythmic puzzle game with a twist.

- Project Giana is a challenging fast-paced platformer with a twist. (Note: this was the tentative title for what’s now Giana Sisters: Twisted Dreams.)

- [Rhythm Destruction is a] unique action packed experience inspired by classic shooters and infused with addictive rhythm gameplay.

Wow. Who knew there was such staggering originality in the indie game and crowdfunded game scenes? …but that’s not truly what’s going on. These are the results of a powerful temptation to invoke the idea of innovation and all the warm fuzzies that come with it. It’s so strong that the Hatland Adventures creators called their game unique twice in the same sentence—but I’m in no place to knock anyone. I’ve fallen into the trap myself, mentioning innovation as a positive in and of itself even in a post that was explicitly about how innovation is immaterial compared to having your own vision. The problem: no one can credibly promote their own originality by calling attention to it. And no one needs to! Take that Rhythm Destruction line and remove one word:

- Rhythm Destruction is an action packed experience inspired by classic shooters and infused with addictive rhythm gameplay.

Space shooters meet rhythm games, huh? That’s pretty interesting. I daresay it sounds unique!—and there’s the rub. When you’re innovative, you don’t need to say so.

2: Real innovation is almost legendary.

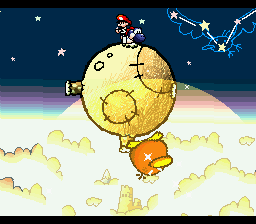

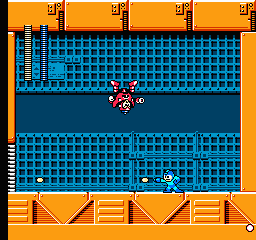

Super Mario Galaxy is hailed as one of the most innovative games ever made; Super Mario Galaxy owes a lot to Raphael the Raven from Yoshi’s Island. Nintendo already had the idea of running and jumping around small spheres in space twelve years earlier; SMG simply fleshed it out to its ultimate conclusion in a full game. Mega Man 5 had gravity-flipping in 1992, long before indie darling (and one of my personal favorites) VVVVVV; Metal Storm had it a year earlier than even MM5. For that matter, M.C. Kids, a licensed NES game using McDonalds characters, had sections of walking on the ceiling. 2002’s Blinx had time manipulation before Braid, but so did 1990’s Catrap. Braid evolved the idea with elements like objects that are immune to rewinding time, but that’s just it—it was an evolution, not a revolution. The core idea had existed for almost twenty years.

It’s easy enough to give you something you’ve never seen before; it’s near impossible to give the game industry something it’s never seen before. If a developer claims to have a fully new idea, it’s likely that the developer simply doesn’t know about the games that have already done it, but nothing is wrong with that. On the contrary, that’s the way it should be; a game developer benefits from playing and learning from hundreds of games, but building an encyclopedic knowledge of gaming is best left to journalists and fans. I can’t begin to imagine the mental energy needed to study every known gameplay mechanic and invent something that’s never once been used. The amount of mental energy needed to sweat the similar stuff is so high that I’d be concerned the developer didn’t have any brain juice left for making a good game.

Game quality is denominated in fun and developers need to think and plan accordingly—not to ask themselves if a feature would be groundbreaking, if it’s never been done before, or even if it’s at least been rarely done before, but only if it would interest the player.

None of this is yet a counterpoint to the RPS article, though. People have no need to promote their own originality or strive for it, but that’s not the same as saying that they should make appeals based on their lack of originality—so let’s get cracking on why it’s perfectly great to do just that.

If you have a Pixiv account, I recommend clicking on this for full size.

I’ll list some dead horses that gamers beat with the “same old stuff” stick: Call of Duty, Madden, JRPGs, first-person shooters, anything with zombies, and bald space marines. In any decently-sized gaming community you can hear comments like “enough with the zombies” or “JRPGs are all the same thing” or “oh, look, another Call of Gun Warfare: Modern Duty clone.” They trumpet that the real creativity comes from indie developers—but what creativity are they talking about? Did Geometry Wars break new ground? Did Super Meat Boy?

Many people say “creativity” when they mean “variety.” It’s a counter-culture dissatisfied with the mainstream. The appeal of giving a JRPG’s main hero an axe isn’t that it’s innovative, but that it’s not a sword. The allure of a brutally-difficult game isn’t that it’s innovative, but that it’s not easy. The excitement of a new point-and-click adventure game isn’t that it’s innovative, but that it’s the one game of its genre in a thousand.

The industry has tilted toward open worlds and sandboxes where a player can do anything and everything in a virtual space, but players want developers on our real planet to do anything and everything as well, making games that cater to every taste. What good is an open world if people don’t sprawl in every direction?

At the time I type this, there’s a possibility that the Voyager 1 spacecraft has exited our solar system. This would be momentous, phenomenal, and everything good. At this point in human history, it’s literally one-of-a-kind.

A video game has no need to be Voyager 1. It’s enough to climb Mt. Kilimanjaro, although that’s been done before. It’s enough to dive 20,000 feet in a submarine; it’s enough to dive 10,000 feet in a submarine. Doing something rare is worth celebrating in and of itself.

.png)