And it’s all similar stuff. I treated the Grand List of Role-Playing Game Clichés like an unchecklist when I spent my time paper-plotting my dream RPGs at the age of sixteen: anything I thought up that I found on the List needed to hit the cutting room floor. Years later, I discovered TVTropes—and if I had treated that like an unchecklist, no game on the planet would remain.

I’ve heard an academic theory that, from a satellite view of screenwriting and literature, they only offer two types of stories: a hero takes a journey or a stranger comes to town. “Hero” is shorthand for “main character”, but I won’t break that saying down further because I don’t devote my time to movies and novels. I devote my time to something far more interesting and this is my theory:

Video games only offer two types of gameplay: Mario and Pokémon. Either circumstances control the hero or the hero controls circumstances. Either a big bad dragon rolls into town and captures a princess, ruining the hero’s peaceful life, or the hero has had enough with peace and sets out to challenge the world and be the very best—like no one ever was. Dragon Quest vs. Etrian Odyssey. Mega Man vs. Street Fighter. Castlevania vs. Monster Hunter. Tetris vs. any sports game ever made.

smaller.png)

The best-selling video game franchises epitomize the basic building blocks of any title in the industry: the two possible goals and roles of the player.

Drill down to details and move from satellite to eagle-eye, but everything under the scope will be seen as an homage to history by the respectful soul or a cornucopia of cliché by an unthawed, cynical heart. Snow levels and fire levels are everywhere except for the games that take place in a city setting with slums and sewers. Outside of the indie scene, game designers rarely get around the conceit of glorifying their own species and only a few exceptions like Kirby and Donkey Kong Country make it big with non-human heroes. Story is even more mapped out than setting and character design. The quest undertaken by the chosen hero of legend is as old as soil and the quest of the everyman who proves that anyone can achieve greatness is as old as sand.

Take analysis to the ground level of characterization, but the most quirky fantasy hero will still find thirty-one counterparts. What people put to paper can’t stretch beyond their imagination. Some types of protagonists and villains show their faces more often than others, but no one has written a character completely alien to all human experience.

In a game or any other creative work, the dividing line between striking and sleepy is measured in fine grains, in the smallest atoms of a creator’s care, concern, and attention to detail. An excellent game gives the shining sense that its creators love gaming, and anyone who loves gaming will demonstrate an appreciation of its history. Those who look down on the past might scoff “stereotype,” but philosophers build on the ideas of Aristotle and Socrates, scientists build on the theories of Newton and Einstein, filmmakers and artists and writers build on every style before their time, and game designers also stand on the shoulders of giants. Discarding all the great works of the past is like jumping into a fire to disprove the common wisdom that it burns.

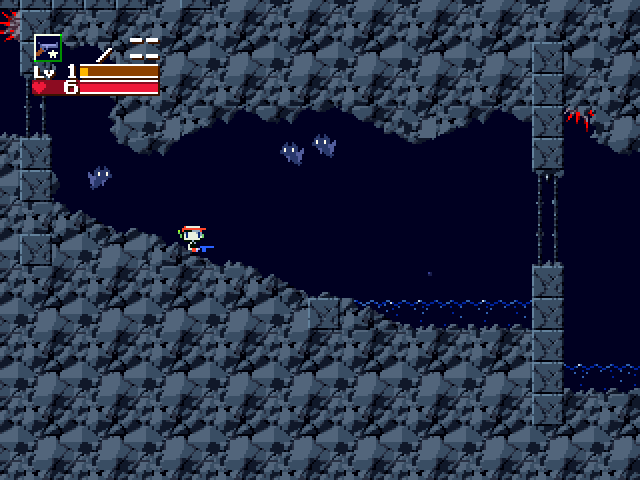

Cave Story’s ability to borrow great elements from Metroid and later Castlevanias and handle them as expertly as Nintendo or Konami is just one reason that it inspires would-be indie developers. I should know.

A game designer who only shows the player that he craves novelty will never impress like a game designer who “only” shows that she loves her characters and her world—and love, like money, is easily denominated in time. Those who prevail are those who ceaselessly tweak every corner of the planet, adjust every law of game physics, touch up every animation, nail every camera angle, and fine tune every line of dialogue, never satisfied after three thousand, eight hundred and forty-seven revisions, forever striving to outperform their own shadows.

It’s not that gamers will explicitly notice the arduous work of the designer; it’s the opposite. Superb game design flows so smoothly and naturally that it becomes invisible. Anyone with fair intuition can identify a rushed, rough-around-the-edges game and when they do, they’ll ask questions like “What were they thinking?” or “Didn’t they test this game before they released it?”

The game developed by a fan has no such rough edges because the heart of an artisan can’t permit their existence. An artisan must create, and the motivation that drives him to perfection is not money or a whip cracked over his head, but his own vision. He presses forward with passion and pursues it like a crazed man because he is a crazed man. Only one fear torments him, but it is the most vivid fear of all: that he will go to the grave with his song still inside of him.

A game designer will stumble over glitches and bugs, and she may complain as she stubs her toe those first few dozen times, but she holds the truth in her heart. She can imagine a future where she never begins to make her game. She can imagine a future where she has zero bugs—and zero bugs would tear her apart. Zero bugs are worse than ten years of bumpy road. So she puts on her steel-toed boots and keeps on, knowing that even if she suffers five hundred setbacks, she takes five thousand steps toward her goal—and that’s five thousand more than the pretender she can no longer stand to be.

There’s nothing new under the sun. So what? Only the classic has any hope to become cliché; no element of any game will become overused without first being beloved. Designers only need to prove that they were gamers first. Designers are free to draw from any new or old school of thought as they please if only they can prove, through the care they sink into their craft, that they love gaming too.

Pingback: Gameplay vs. Story: The Catch-22 of Permanent Missables | Game Design and Deconstruction

Pingback: Gaming Innovation: Mythical. Gaming Diversity: Magical. | Game Design and Deconstruction